One More Rep.

How the internet pushed fitness enthusiasts to failure before they even started

The current, 'digital age' is dominated by easily digested content. Streaming services are slowly forcing television to take a backseat, as the modern-day consumers’ desire to pick and choose what they watch, increases.

As the desire for specific yet simple and entertaining content rose, the public took to YouTube as a platform to broadcast their expertise on niche topics.

Today, TikTok dominates the social media scene, with millions of short, simple, entertaining videos being posted each day.

One of the most frequently posted hobbies posted on these platforms, is fitness. Creators can publish their own tips and tricks based on their own experience to help beginners and experts alike.

It all sounds good, but unfortunately, the lack of regulation of content posted on these websites means that misinformation and exploitation is extremely common.

This couples with enhanced imagery of influencers in perfect lighting, posing, flexing, with a pump, meaning they don’t look anything like how they do in real life. Some of these influencers even take PEDs but claim they don’t, to even further mislead and exploit their audiences.

The online fitness industry had the potential to be a constructive, informative realm for people looking to develop their new hobby. In some places, it is. But it’s now also plagued by misinformed, thoughtless, money-hungry narcissists, who will go to any lengths to promote themselves or make a bit of extra cash.

The bad, the good, and the ugly.

Online fitness advice

Online fitness advice has never been more prevalent than it is now. When we were plunged into lockdown in 2020, millions of people turned to the advice of online trainers, so they could work out at home. However, a large portion of online advice is just plain bad.

It’s easy to label something as ‘bad’, but what actually is it about online fitness advice which is causing confusion and frustration among those trying to educate themselves?

Matt started going to the gym when he was 16 and felt overwhelmed by the amount of information available to him on YouTube. He discovered a channel with a huge following created by a qualified trainer and began watching the videos in order to educate himself on how to train properly. Interestingly, this didn’t work out in his favour.

“You think you’re doing everything right, because you don’t have the knowledge to know if you are or not.

“You’re just entirely relying on these people that are telling you what to do.”

Matt followed advice he found on YouTube when he started going to the gym. He said it was “demoralising” when he realised the advice that he’d committed to following, wasn’t helping his progression.

“It just didn’t encourage me to continue at all… I found it very difficult to commit because it was such slow progress.”

He attributes his lack of progression as a beginner to the fact that the YouTube videos and channels he followed, failed to educate him on essential recovery factors.

“There’s not really a big emphasis on diet on channels like that either, or just anything else that’s super important like sleep and stuff like that.

“It’s just a very inefficient way to progress.”

Although many aspects of fitness advice are heavily solidified by science, there are some topics that are more subjective. For a beginner like Matt, this can be very confusing. Contradictory information makes it exceptionally difficult to figure out what’s right.

This leads to new gym-goers feeling lost, and self-conscious that they’re doing something wrong in the gym.

Some advice can not only be confusing, but factually incorrect. To find some examples of incorrect fitness advice and ideologies posted and promoted on YouTube on TikTok, is actually very easy...

A professional bodybuilder with a combined following of over 80,000 across TikTok and YouTube, posted a TikTok in February 2022. In the TikTok, he explains how he trains to failure on every set. This means at the end of each set of his workout, he is so burned out that he is physically unable to do another rep. His reason for this?

“The closer proximity to failure that you can achieve… the more muscle you are going to recruit.” He says.

He justifies training to failure on every set by saying “I’m trying to get the most bang for my buck.” This creates an implication that training the way he does, is the best way to gain muscle.

Dr Mike Israetel holds a PhD in Sport Physiology, and is a former professor at Temple University, Philadelphia. He has several published articles and books on training. Dr Israetel’s research shows that reaching failure on every set actually has a negative impact on muscle growth (hypertrophy).

Videos like this have created a common notion that you should ‘push yourself to the limit’ regardless of experience level. This is likely because it makes people feel like they’re working harder, which they are, but according to science, this way of training is pointless and risky.

There are also several smaller creators, especially on TikTok, who post blatantly incorrect advice. The TikTok algorithm means these videos from creators with no credentials can reach thousands, sometimes millions of people, many of whom will take it as fact with no further research or deliberation.

Joe Delaney, a YouTuber with over 500,000 subscribers, posts educational content about bodybuilding. He likes to keep things clear for his audience by using simple science to back up his points. Joe is one of the best in the game at this, and emphasises the importance of keeping things straightforward.

“People aren’t even going to read a study.”

“If someone can understand the simple version, and the simple version is eighty-ninety percent as good as knowing all the finer details, then that’s much better than them just listening to you and switching off completely because you’re reading like verbatim.”

Joe likes to “dumb down” complicated scientific studies to a level that anyone can understand them in his videos.

He recognises the amount of contradictory and confusing content online, and puts a large amount of it down to “a lack of evidence”.

“There’s no huge financial bodies supporting research on how to get a bigger chest.

“Because there’s a lack of that, that space gets filled with opinion.”

Advice from the experts...

Despite the sea of incorrect or contradictory information available on YouTube and TikTok, there are some creators who post clear, informative content which is backed by science to prove its efficacy. From the interviews conducted, it seems clear that, in order to create complete content, creators need to speak about all aspects of the gym, including training, but also diet, recovery, and maybe even mindset.

Joe Delaney recommends Jeff Nippard’s channel, labelling Jeff as, “the epitome of informative fitness content.”

“He does the best he could do it. Could you do it better than that? I don’t think so.” He said.

Body Dysmorphia: An epidemic

These two pictures were taken 90 minutes apart. All I had to do to ‘transform’ my body, was get some blood in my muscles by working out, suck my stomach in, flex my muscles, and add a filter. This is how influencers look the way they do in their pictures. In reality, they don’t have a pump, and are not posing. They look completely different.

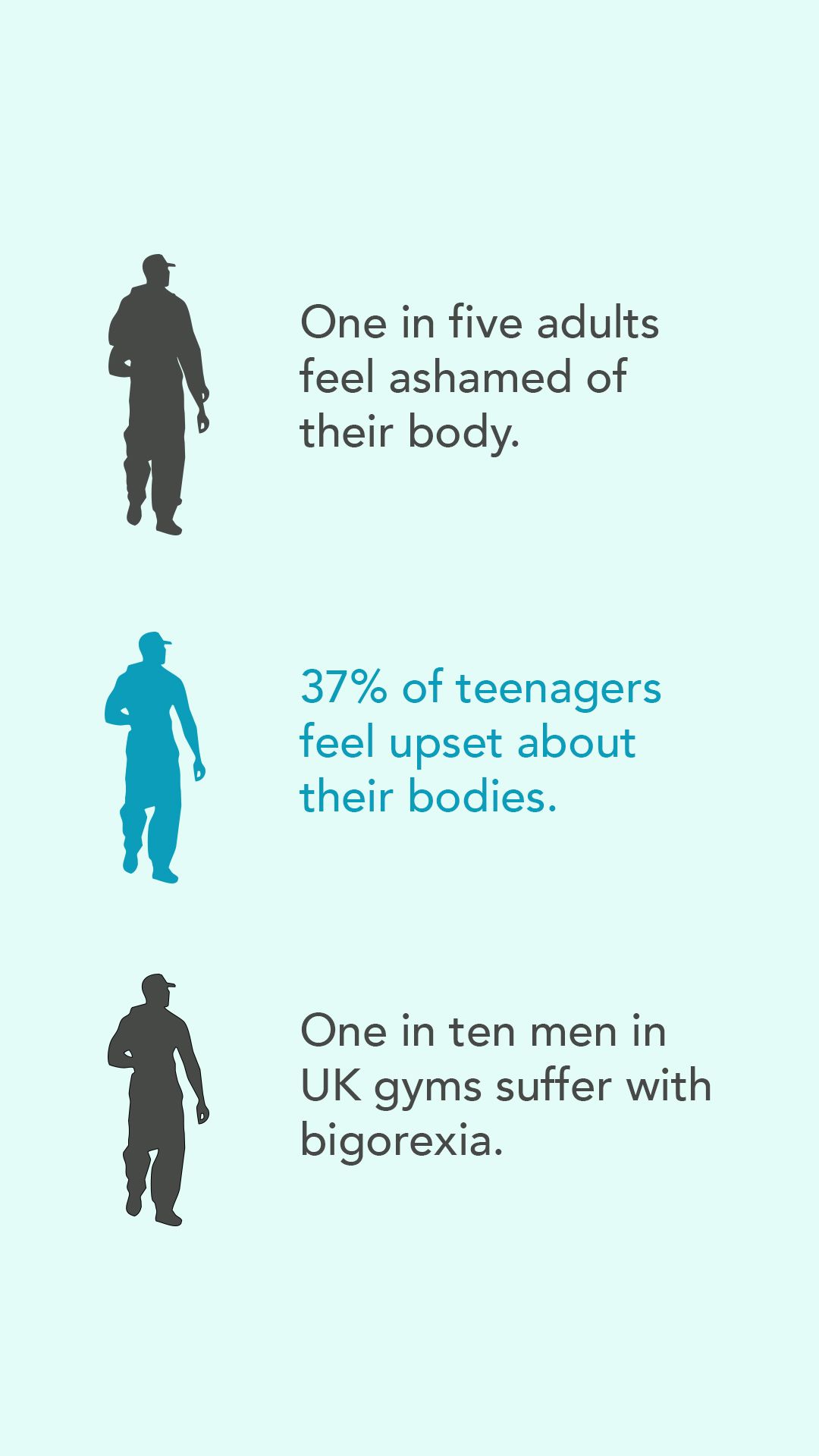

Mental health issues surrounding body image have become commonplace in our society. It’s widely accepted that magazines airbrush their pictures, and supermodels starve themselves to become skinny. Since the rise of social media, this problem has only become worse, and has now started to affect men as well as women. In 2019, a survey by the mental health foundation found that one in five adults felt ashamed of their body, and 37% of teenagers felt upset about theirs.

In the realm of fitness, magazine covers with enhanced bodybuilders posing in perfect lighting, with blood pumping through their muscles, and often with a little help from photoshop are normal. Many actors use performance enhancing drugs to drive their physique to unattainable levels for roles in Hollywood movies, but don’t specify their PED use. This onslaught of what society has begun to think is perfection, now leads regular gym-goers to feel bad about their bodies, and not understand why they are not making progress at the same rate as their favourite cover models and movie stars.

As a result, a body dysmorphia epidemic began.

Some have referred to body dysmorphia among fitness enthusiasts as ‘bigorexia’. Many gym-goers are constantly striving to be bigger, and never happy with how they look. Many even see themselves as too ‘skinny’ or too 'fat'.

According to a BBC News article, it’s estimated that 1 in 10 men in UK gyms suffer with the condition.

It has now become a serious problem in our culture. The issue of unrealistic body expectations has since been exacerbated by social media, especially YouTube and TikTok.

Harry is a 22-year-old student, who lost over 25kg through dieting and working out with cardio, due to dissatisfaction with his health and looks. He set out on his weight loss journey with the goal of looking like some of his favourite influencers.

“Seeing unrealistic body standards on Instagram and YouTube and stuff, they’re putting out an unrealistic image.”

He quickly began to realise many of the bodies he’d seen on social media were actually naturally unattainable.

“It’s a bit infuriating.

“Influencers often say you can attain these ‘perfect’ sub-10% body fat physiques naturally, which is obviously untrue.”

Luckily, Harry realised this early on, and modified his expectations to avoid aiming for an unreachable goal.

He used an unrestrictive diet method, in which he allowed himself to eat his favourite foods like McDonalds, alongside playing basketball and running to burn calories. He believes this is a healthier approach than restricting and obsessing over food intake.

“I think that instead of just restricting yourself so heavily with calories… doing cardio is a lot more beneficial to not only the weight loss but also your cardiovascular health.”

Harry feels good about himself after his hard work paid off and believes his mental health has actually improved due to his reasonable approach to reaching a healthy bodyweight.

“Just actually losing the weight and staying at a normal bodyweight is fine for me to be honest. I’m quite happy with where I’m at, at the moment.”

Sadly, not everyone who sets out to change their physique is as well informed as Harry. Many do not realise how the bodies they see on social media are just a snapshot of what that person actually looks like.

Nerissa Shaw is the Clinical Lead at Somerset and Wessex Eating Disorders Association. She often treats patients with body dysmorphia who are also fitness enthusiasts.

“I never would say don’t get fit or don’t try to change your body shape if you think that’s what will make you happy, but it probably won’t make you happy, it might make you feel better and it might be good for you but beware of becoming a slave to that.”

Shaw expressed her disdain for influencers who mislead their audiences with their enhanced bodies to promote and sell programs, supplements, and other products.

“It’s really harmful.

“Selling something like that to vulnerable people is really wrong.

“We can’t really help but be influenced by those things [pictures]."

She also highlighted how body image issues and eating disorders often affect people that have already seen success in the realm of fitness.

“They’ve been successful in getting fitter or losing weight, and then anxiety starts to creep in about well how am I going to maintain this? And before you know it they’ve developed a full-blown eating disorder.”

The term fake naturals, or ‘fake natties’ has become a commonly used phrase among the YouTube fitness community. It’s used to describe someone who lies about not taking performance enhancing drugs. These sorts of influencers lead their audiences to believe that they can also achieve their naturally unattainable physiques, and often use their physiques to promote products such as supplements, programs, or clothing.

A YouTuber from London by the name of Brandon Harding was accused of using steroids in response to his ‘natural transformation’ video, which showed his progress from skinny to muscular over a short period of time. This led to many hate comments encouraging Brandon to disclose that he was very likely using performance enhancing drugs.

In 2017, he admitted to using steroids to help build his impressive physique. Interestingly, this confession was not met with hate or malice, but immense respect. It seemed the fitness community was so refreshed to have someone be honest about their PED use, that they were willing to forgive him almost instantly. He took ‘natural’ out of the title of his transformation video, and favourited encouraging comments from his subscribers.

One comment from ABlue Biker, read: ”YES BRANDON LAD. So glad you spoke with such honesty man. Even more respect, as I was starting to lose some for you, but its just gone through the roof for you again my man. Much Love."

In January 2021, Noel Deyzel, a professional bodybuilder and popular influencer with over 4.6 million followers on TikTok, posted a video disclosing his steroid use. In this video, he urges other influencers to do the same, stating that they “risk other people’s health for their financial gain”.

“These same influencers enrich their lives by promoting and selling you their diet and training plans, making it seem naturally attainable to achieve their chemically unachievable physiques.”

The video received overwhelming support, amassing over 560,000 likes.

So, it’s clear that fitness enthusiasts don’t care if people use performance enhancing drugs, but they do care if they don’t disclose their usage of PEDs to mislead their audiences. But PEDs aren’t the only way people have been misled by influencers on social media.

On TikTok, an influencer by the name of Alex Eubank has amassed 1.4 million followers by posting videos which showcase his chiselled physique. However, some of his fans noticed imperfections in his Instagram pictures, and some of his videos, and began accusing him of PhotoShopping his physique.

He eventually admitted to this, which was met with huge backlash, as he had gained such a large audience in such a short period, who now felt misled and tricked. A Reddit user posted in the r/nattyorjuice thread and stated, “It’s literally as cringe as being a fake natty”.

So mainstream media, Tiktok, and YouTube have all played a role in contributing to widespread body dysmorphia, but as usual, retailers also had a part to play.

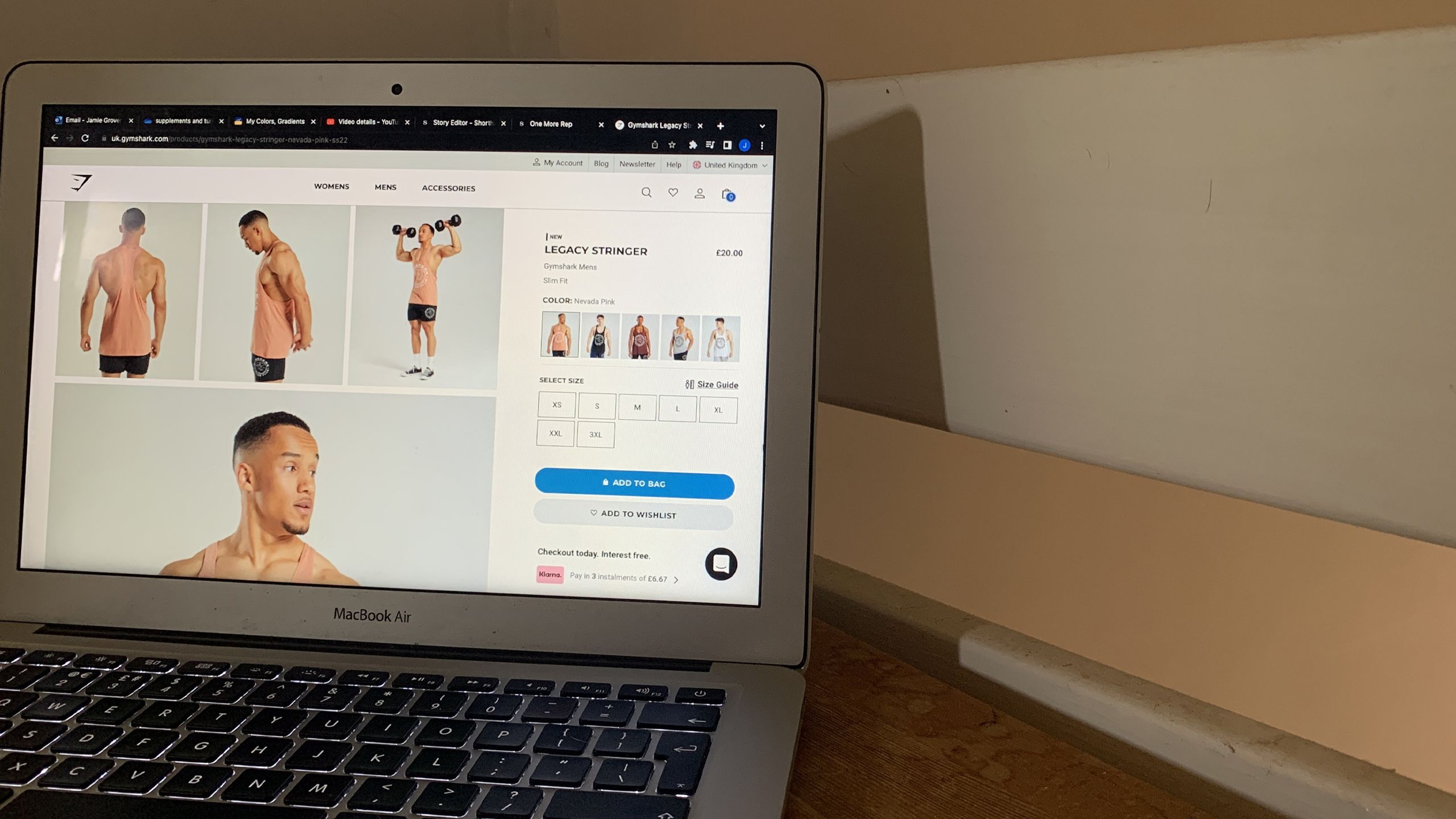

A popular clothing brand among fitness enthusiasts, known as GymShark, made their name by signing popular YouTubers to be models for their clothes. This meant the GymShark website was filled with images of people with ‘perfect’ physiques, which made the clothing more desirable.

A selection of these athletes have since admitted to their usage of performance enhancing drugs. Although this is not illegal in most cases, it is ethically questionable. It gives their followers false hope of one day looking like their favourite YouTubers, when in reality, it would be physically impossible for them to look like they do without the aid of performance enhancing drugs.

The brand has since made the progressive decision to use models with attainable and natural physiques to model their clothing. Interestingly, this decision has been very divisive among GymShark fans.

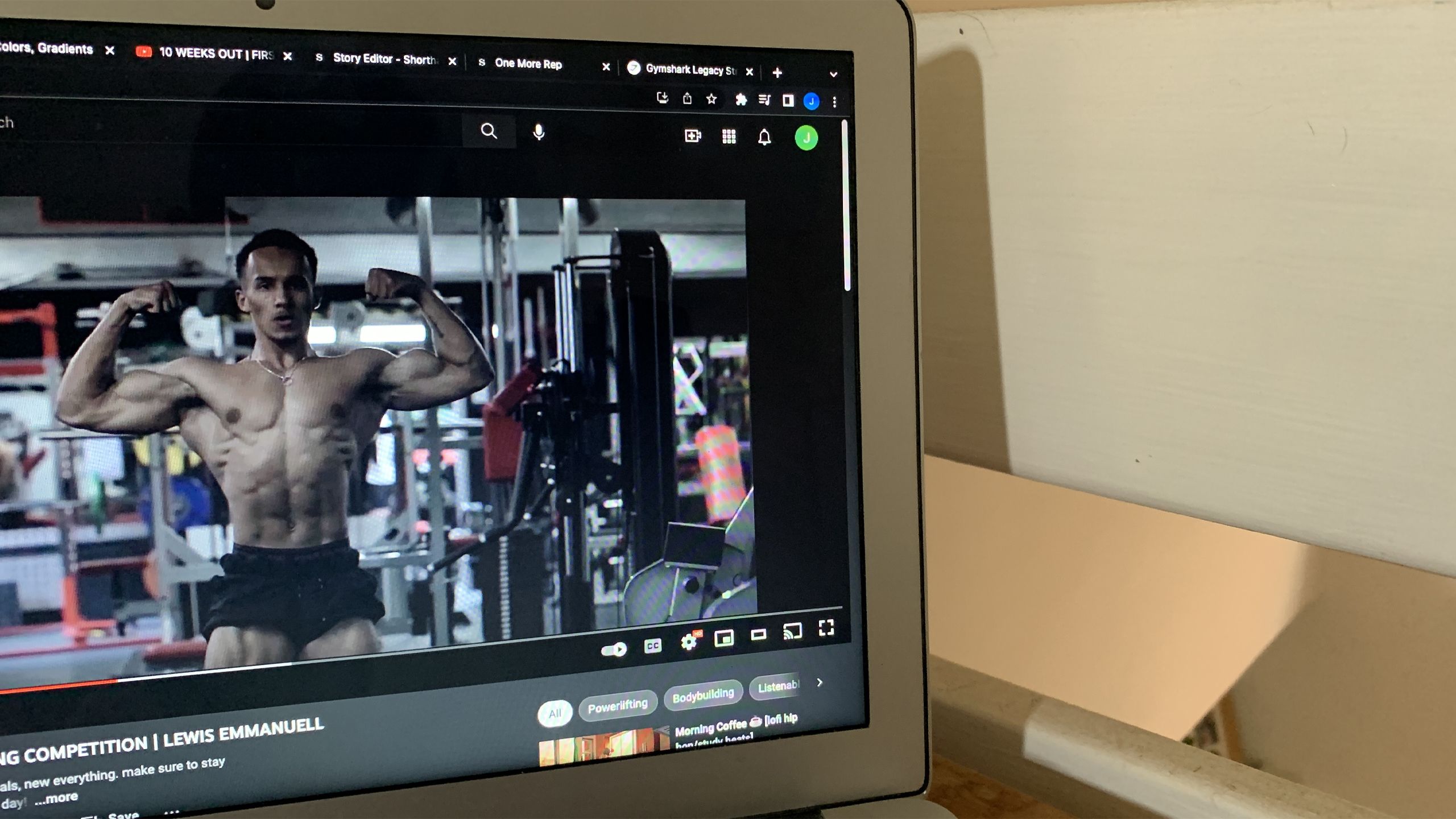

Lewis Emmanuell, a 19-year-old GymShark athelete, was part of the shoot which received backlash from some GymShark fans. He gave some insight into the brand’s current approach, and also expressed why he felt his shoot received a negative reaction.

“If they start to promote people that are unattainable, people are going to think this is attainable when it’s not."

“People ask: ‘Oh my god you need to stop showing people with unattainable physiques, people that are using PEDs.’

“When they go: ‘Okay cool, we’re going to listen to what you guys have said.’ … people go ‘No no no not that they don’t even look like they go gym.’”

Lewis also spoke in reaction to some former GymShark athletes who publically expressed their disdain for the shoot.

“They have such a fanbase right, that you can almost call it a cult.

“They weren’t there in the picture, if they didn’t say anything and they were supporting and promoting, I promise you we would’ve had minimal, minimal, minimal amounts of hate.”

It is hoped that GymShark’s recent switch to ‘body positive’ models, many of which still have jaw-dropping physiques, will encourage consumers to realise that clothes are for everyone, regardless of what stage they’ve reached in their fitness journey. The brand even told their customers posting derogatory comments towards their models to unfollow them.

Advice from the experts...

Luckily, there are ways to enjoy fitness without focusing too much on how you look.

- If you find your social media feeds flooded with pictures of people with ‘perfect’ chiselled physiques, it’s likely you’ll start to doubt your own body image, when in reality, these people only look like they do in pictures about one percent of the time. Take this into account when digesting this sort of content, and if it doesn’t help, take a break from social media.

- Try to identify influencers who are likely taking PEDs without disclosure, and recognise that although their content may be entertaining, you shouldn’t aspire to look like they do if you are a natural trainee. Sometimes it can be demoralising to accept this, and if you find yourself losing motivation or passion for fitness, it might be time to stop watching a few of these influencers.

- A good method of finding out whether someone is natural or not is by watching Greg Doucette’s ‘Natty or not’ series on YouTube, in which he uses a mixture of his own judgement and reasonable evidence to suggest whether someone might be a fake natural. A Reddit thread titled ‘r/NattyOrJuice’ is also a good way to discuss and form your own opinion on this matter.

If you are struggling with any sort of body image issues, there are a range of charities like SWEDA which can be found online and will be more than willing to listen to your concerns. Nerissa Shaw recommends trying to recognise how your looks may not affect your self-esteem as much as you think.

“Think of some of your friends, is how they look important to you?

“Most people would say no actually it’s not very important to me at all, and that works in the same way, people are not necessarily that interested in how we look.” She said.

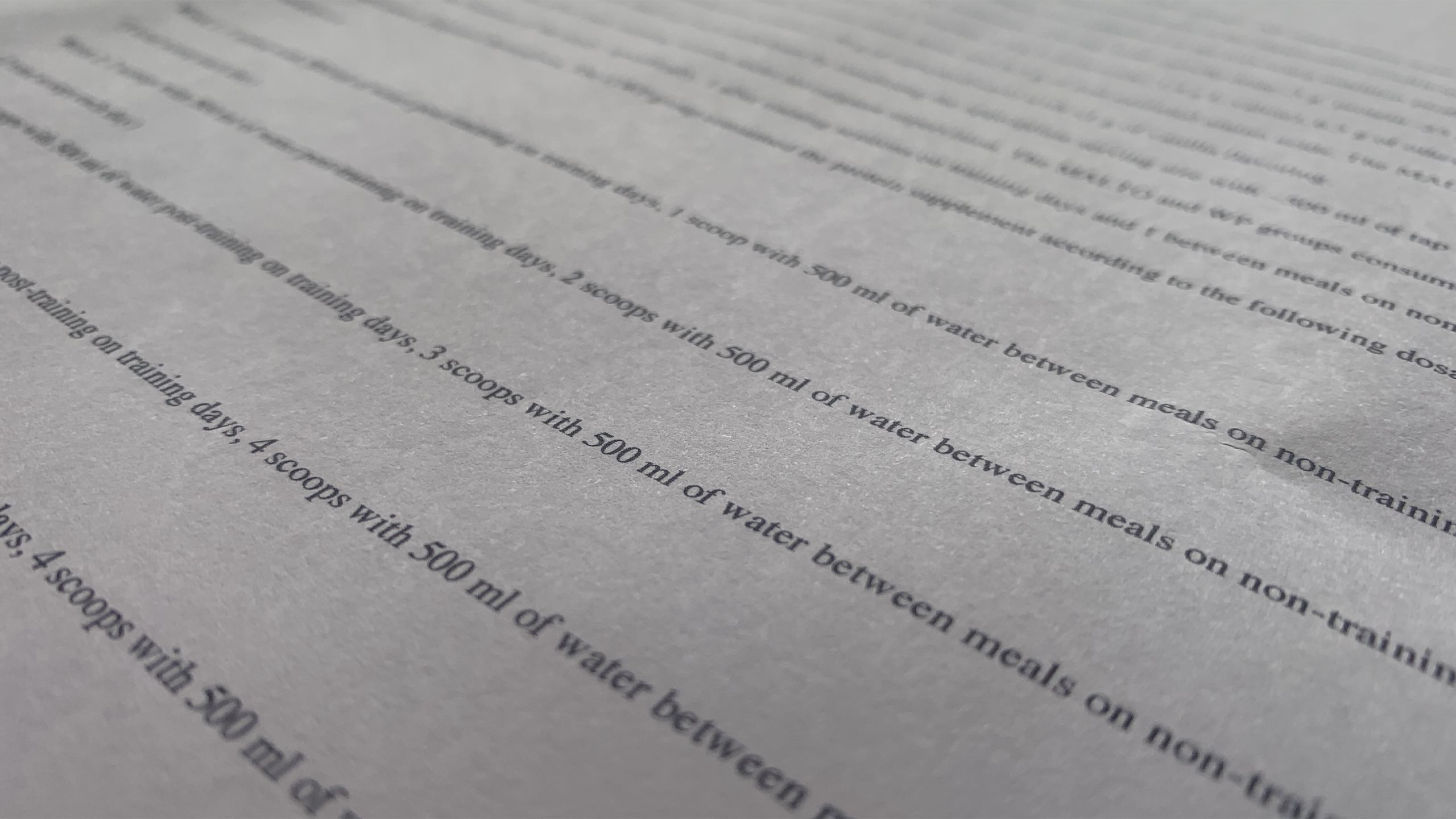

Supplements

Not actually shortcuts

Supplements are often glorified in the fitness industry as a sort of short-cut to reach your goals. The harsh reality is, no supplement will help your progress unless you train consistently and eat well over a very long period of time. Some supplements may even provide little-to-no impact whatsoever.

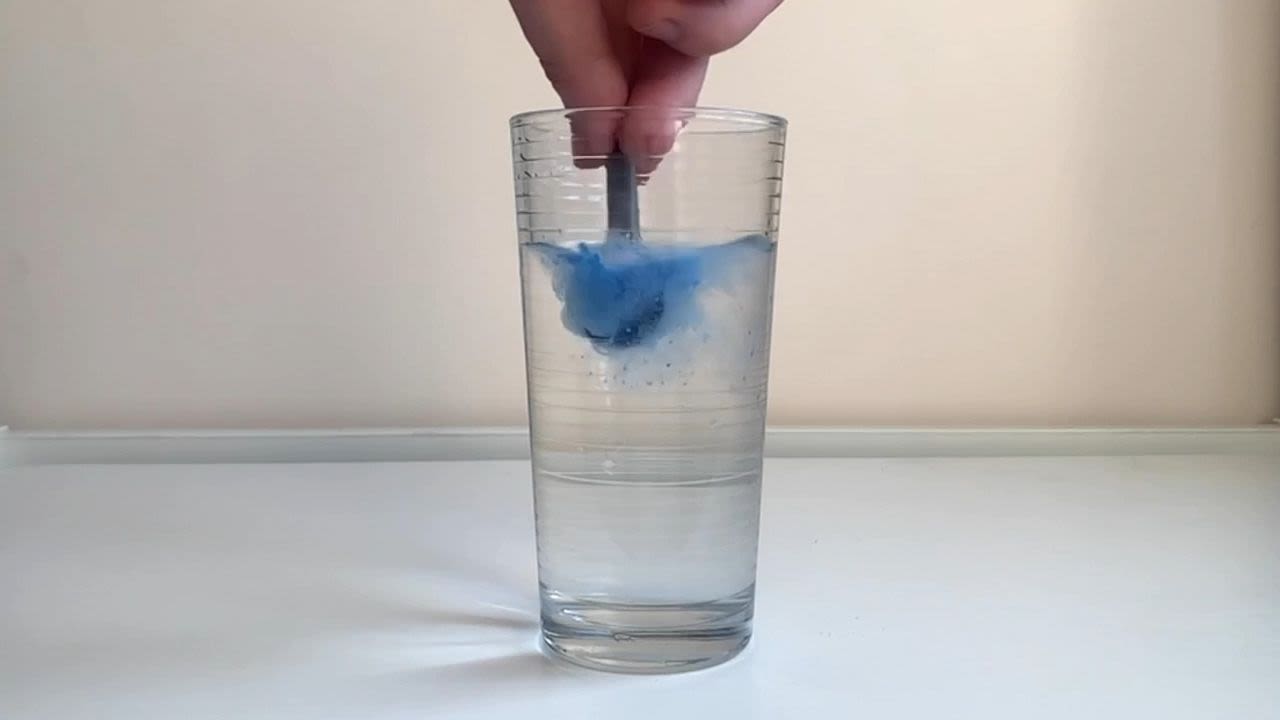

Creatine is the world’s most widely researched supplement. It has been proven by over 500 studies to be safe and effective with no side effects. A daily dosage of this supplement has been shown to increase ATP in your muscles; effectively meaning better muscular endurance so you can squeeze out a couple more reps. It also means better muscle recovery, and more water being held in the muscles which creates a ‘full’ looking effect.

There are several reputable retailers which sell these effective and safe supplements. Although their effects may not be majorly noticeable, they can help to ‘optimise’ your training.

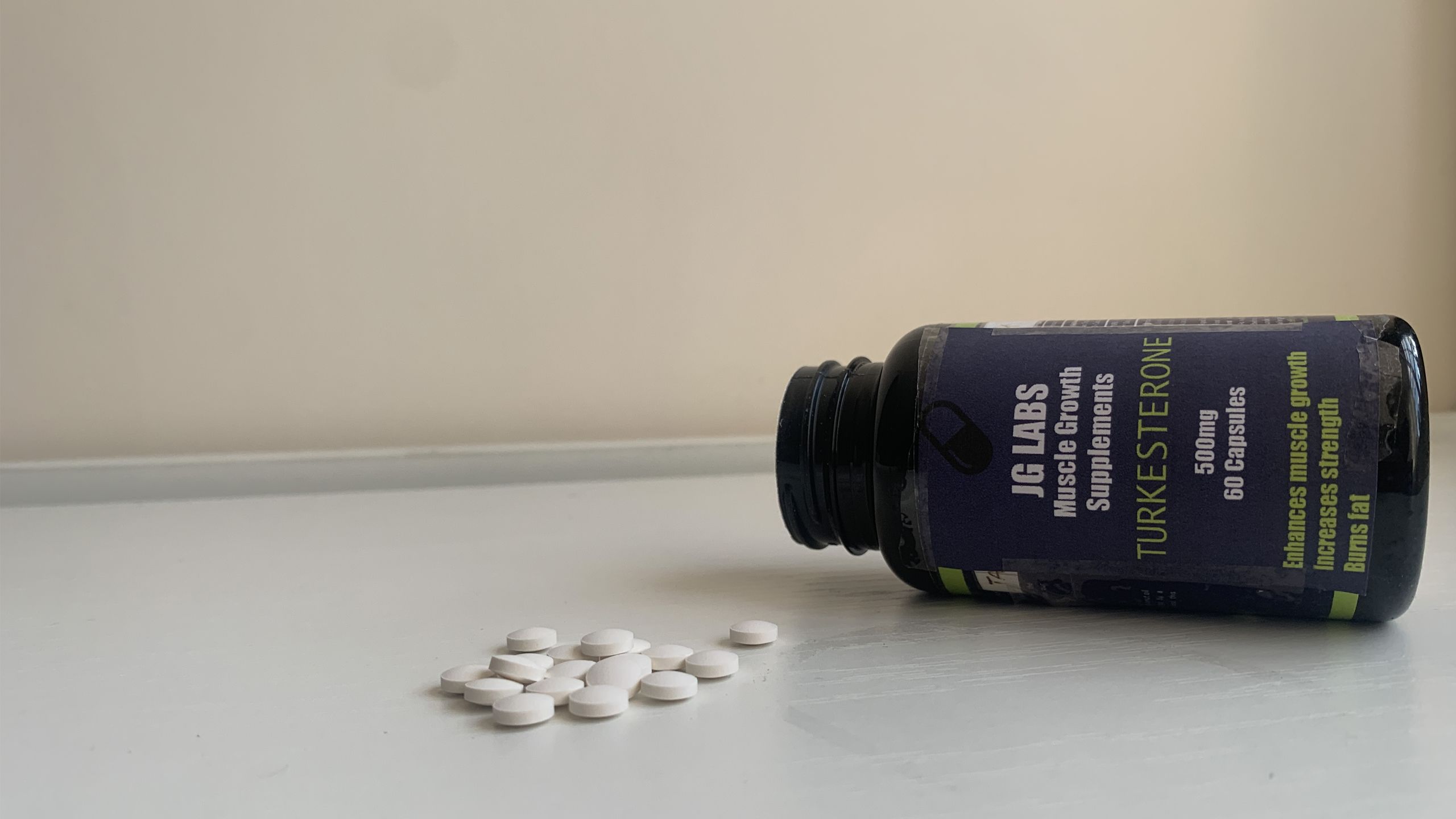

At the other end of the scale, is turkesterone. A supplement concentrated from spinach leaves. Many retailers which sell turkesterone claim that it increases your muscle mass and strength. However, a severe lack of research into the substance means these claims cannot be solidified.

Ben started taking turkesterone when he started lifting weights to help him maximise his training and get as big and strong as possible. He has since stopped taking the supplement and believes the money he spent on turkesterone was wasted.

“I saw loads of videos online… they were saying this magic pill is the same as steroids. I was like what the hell, this is crazy.”

“It was pretty expensive, it was like 70 quid for two bottles.

“I pretty much thought that what it was, was just a placebo really.”

He found out about turkesterone when he saw videos about it on social media.

After six months of taking the supplement, he stopped taking it. Half a year later, he’s noticed the lack of turkesterone in his system has caused no negative effects to his physique or strength.

“I did feel good on it but I don’t know if it was because I was on it, or just because I was taking some pill.”

Turkesterone has recently surged in popularity due to platforms like YouTube and TikTok, where creators with large followings are talking about it

On TikTok, short, easy-to-digest clips outlining the supposed benefits of the supplement are commonplace. After some light research, it’s evident that most of the creators of these videos have ties to a retailer which sells turkesterone.

On YouTube, some creators with millions of subscribers’ post ‘reactions’ to people’s claimed 30-day transformations whilst taking turkesterone, whilst others are more sceptical of the supplement, and try to educate their audiences on it.

Perhaps the man who kickstarted the turkesterone craze is Greg Doucette, a widely praised YouTuber with over 3 million subscribers known for posting content to make people aware of potential ‘fake natties’, whilst also posting his own bodybuilding techniques and advice.

Although Greg does post some respected content, especially his series outing people for hiding their PED use, he is also an advocate for turkesterone.

He has uploaded almost 15 videos on the supplement in the past year. When questioned on its efficacy, he often dismisses the lack of evidence by saying ‘Maybe it’ll work for you, maybe not. I don’t know!’. However, he does not make any explicit false claims about its effects, urging his followers to make their own decision on whether to take it.

Greg, among many other influencers who support the supplement, sells turkesterone through his online shop.

Interestingly, Greg recently deleted the majority of his turkesterone videos after coming under fire for mislabelling what was in his 'Turk builder' supplement.

There are a number of retailers selling turkesterone which explicitly state that it increases muscle mass and strength, despite there being no concrete evidence for this. In fact, the overall research done into turkesterone is worryingly sparse.

A U.K based retailer known as ProHormones has a ‘guide to turkesterone’ on their website, which cites almost all of the available published literature on the supplement to back up claims that it “enhances muscle growth”, “increases muscle recovery”, and “helps increase strength”.

The ‘guide’ cites nine studies, one of which has been deleted, and none of which are peer reviewed. Seven out of the eight remaining studies use rats or mice as the subjects to prove that turkesterone increases protein synthesis, and in some cases ATP (which is what creatine does).

Protein synthesis is the rate at which your muscles can absorb protein for recovery. Essentially, increased protein synthesis means increased recovery leading to increases in muscle growth and strength. It is worth noting that all humans experience a natural increase in protein synthesis after a workout.

There is no evidence in these studies to suggest that the increase in protein synthesis in the rodent subjects is comparable to or even close to the natural increase humans experience after training.

The guide also cites a study using humans as the subjects. This study doesn’t actually use turkesterone, but a similarly structured ecdysteroid called peak ecdysone.

- The study used 46 participants of the same height and weight.

- One group of trainees took 2 pills of the ecydsteroid per day, another took 8 per day, while the remaining group were given a placebo control substance.

- They all completed a 10-week training program and ate the same diet.

- After 10 weeks, results showed a larger increase in muscle mass and strength in the ecdysteroid groups vs the group taking the placebo.

There are many problems with this study however…

1) The body composition of the subjects wasn’t recorded at the start of the program, meaning there was almost certainly a variety of muscle masses and body fat levels despite all the subjects weighing the same. It’s proven that trainees with more body fat find it easier to gain muscle, and trainees with less muscle also find it easier to gain muscle. As all the subjects weighed the same and were the same height, the likelihood of these ‘easy-gaining’ higher body fat, lower muscle mass participants being in the groups taking the ecdysteroids is very high.

2) All the subjects were said to have had a year of strength training prior to the study. However, there was no way to track their progression during this period. Some of the participants may have made more progression in this year prior to the trial, meaning it would be harder for them to gain muscle during the 10-week program. Those who made less progress would find it easier to gain muscle and strength. This is due to the universally recognized and proven phenomena of ‘beginner gains’, where untrained humans can gain an astonishing amount of muscle whilst losing fat at the same time. How likely is it that the ecdysteroid groups contained subjects with lower muscle mass, higher body fat, and less training experience? These subjects would have a substantial advantage over their peers despite having the same height and weight.

3) At the end of the study, the results were found by measuring the subjects’ body composition using bioelectrical impedance analysis. This method is known to be largely inaccurate. A metanalysis entitled ’Is bioelectrical impedance accurate for use in large epidemiological studies?’ concluded that a study using BIA in the way that the human ecdysteroid study did, ‘will not be reliable’. (Dehghan, M., Merchant, A.T, 2008). One of the studies into this method of measurement by Slinde F, Rossander-Hulthen L (2001) found that the body fat measurements from the tested BIA machines was inaccurate by an average of 9.4%.

4) Dr Eric Trexler (PhD) questioned the small sample size of the study, stating ‘What if there’s four people with insane genetics in one of those groups?’. He also noted that the pills used in the study were labelled to have 100mg of peak ecdysone per pill, but actually only contained 6mg.

I then found out that this human-based study was commissioned by the World Anti-Doping agency. I contacted them to find out whether they planned on banning the ecdysteroids (including turkesterone) from competitive sport in light of their findings from this study.

In their responses, the Anti-Doping Agency stated they had no plans to add turkesterone or ecdysteroids as a group to their prohibited list, because they don’t satisfy two of the three qualifying criteria:

1) It has the potential to enhance sport performance, 2) it represents an actual health risk to the athlete, 3) it violates the spirit of sport.

‘‘The use of ecdysteroids in sport is being closely monitored but has yet to reach the threshold from an evidential perspective for satisfying the criteria for their inclusion on the prohibited list.” This essentially means the Anti-Doping Agency haven’t banned turkesterone because there isn’t enough evidence to prove that it actually works.

When questioned on the results from their ecdysteroid study which although likely false, DID provide results that the supplement worked, they stated the following:

‘From a scientific perspective, it is difficult at this stage to draw firm conclusions from the one research study to have investigated the effects of ecdysterone in humans. Nevertheless, further attention is warranted to establish its potential as a doping agent and to verify the findings of the 2019 study that you refer to.’

Dr Eric Trexler recently spoke about this particular study, and turkesterone in general, on the Jeff Nippard podcast. Eric has a PhD in movement science and has published several peer-reviewed papers on bodybuilding.

“With any small sample study in this particular area of research… the risk of false positives always has to be at top of mind.” He said.

“They did an independent analysis of the product’s ingredients and found that the active ingredient was only maybe six percent of what was labelled."

He also commented on the study’s method of measuring the results, using bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA).

“There’s a significant amount of error associated with that particular body composition measurement.”

Dr Trexler then brought to light a worrying issue about influencers and retailers selling the supplement.

“The burden is on the companies to reassure their consumers first of all, that their turkesterone product contains turkesterone, that it contains the amount of turkesterone that is listed on the label, and that, that amount of turkesterone is ergogenic; that it actually enhances performance or body recomposition in human beings.

“Most companies currently fall short of all three of these criteria.”

So ProHormones collated these studies for their guide, which are all either irrelevant or in one case, likely to be a false positive.

They’re selling turkesterone for £34.99 per bottle, with a recommended dosage of two capsules per day. This means one bottle will last 30 days, equating to £425 spent per year.

This is just one of many examples of ways that unreliable supplement companies can manipulate information to create false claims with a clear intent of misleading their consumers. Of course, consumers should do their own research before purchasing a supplement that they do not know about, but the ethics of these retailers are still questionable.

Advice from the experts...

Not all supplements are bad, but it is advised to be careful when choosing what to take, in order to preserve your money, and also safety. Dr Eric Trexler recommends the following supplements to optimise your training.

1) Creatine: “A good bet for strength and performance.”

2) Protein powder: “Only if you’re struggling to get sufficient or high-quality protein into your diet.”

3) Multivitamin/Omega-3 fatty acid product e.g fish oil or algae oil.

In terms of what Dr Trexler classifies as “second-tier specialised supplements”, for competitive athletes, he recommends caffeine before workouts, beta-alanine, or citrulline-malate, with their suitability depending on the way you train.

He notes that these supplements have small effects that “would only be important if you are really really mad about making sure that you are maximising and optimising everything you are doing.”

Progression or regression?

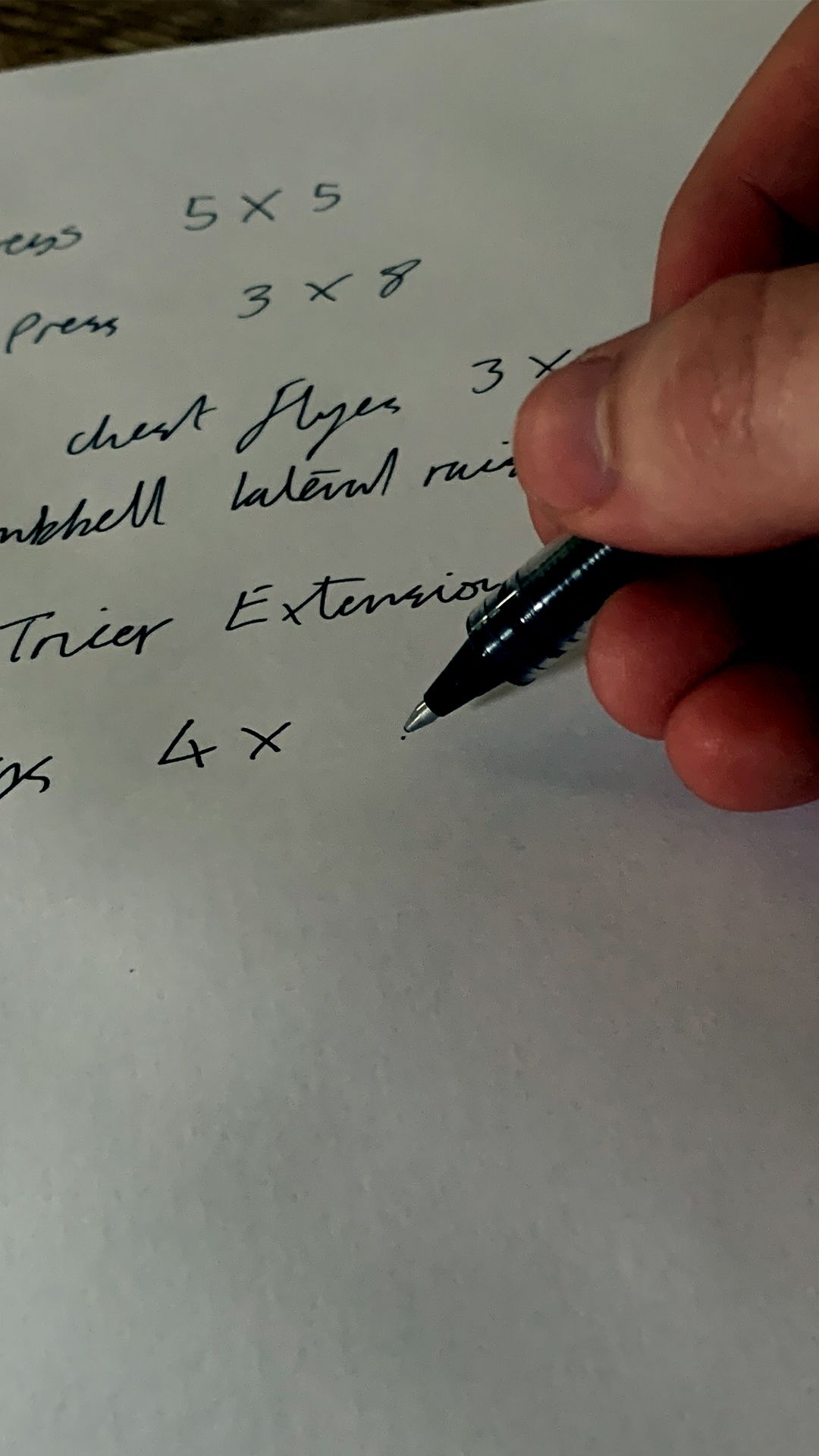

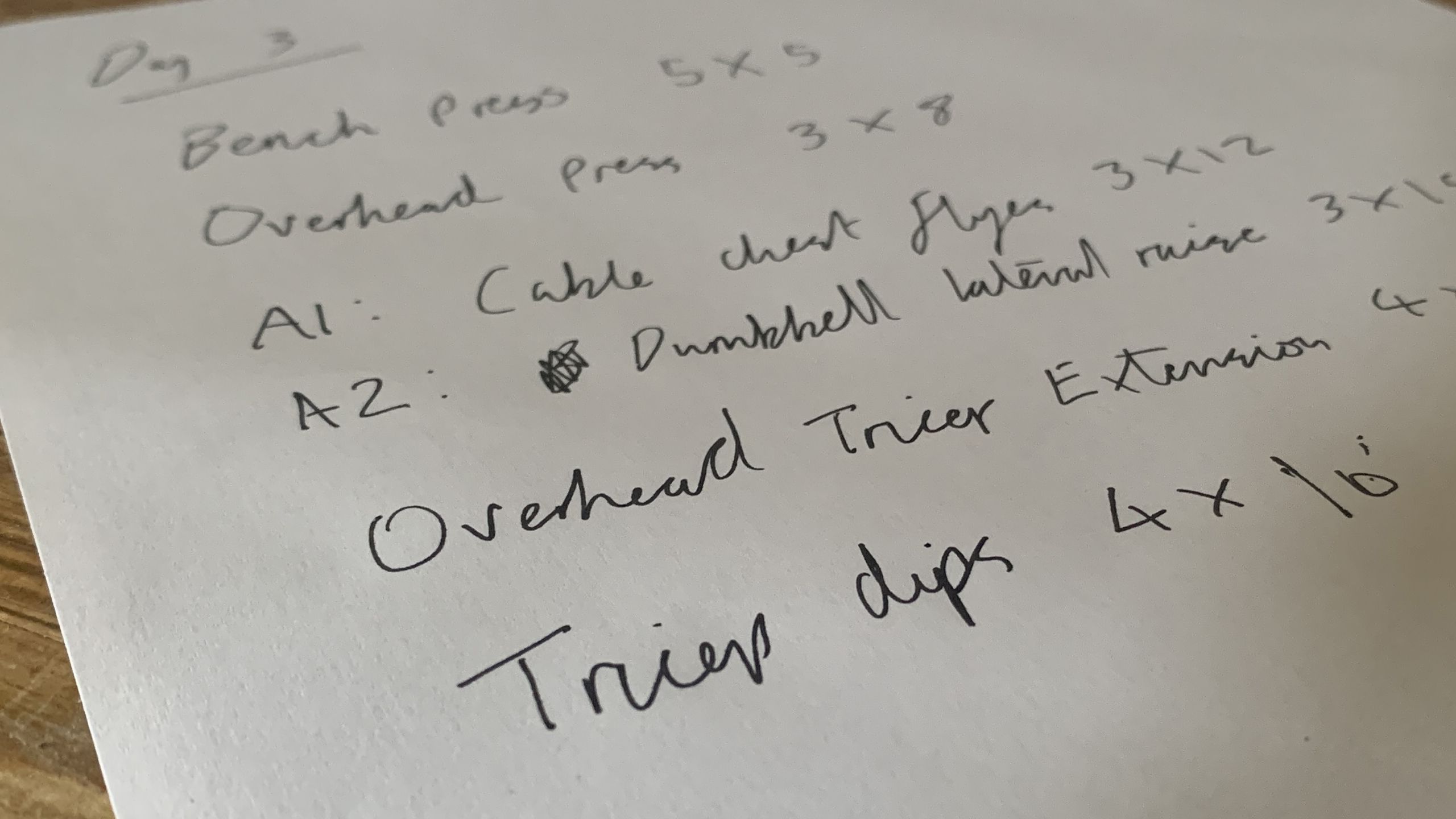

Poorly constructed programs online

A fitness program is a plan which entails a list of exercises with specified sets and reps for an individual to carry out each day. They can often be incredibly effective, especially for people who do not know much about programming or how to train effectively. However, they can also be extremely detrimental and sometimes a complete waste of money.

These sorts of programs used to be common in popular fitness magazines, the sorts you can pick up in most supermarkets. They’d use a picture of a famous athlete or movie star in the shape of their life, accompanied by a caption like ‘Here’s how _____ got in shape for his new role in ____). In Hollywood, it’s not unusual at all for actors to be put on a dosage of PEDs like testosterone boosters or steroids, which means their capacity for recovery goes through the roof. This meant aspiring kids were following along with high volume and high-intensity workouts and seeing no results, or even worse, injuring themselves.

Many influencers in the fitness industry sell their own training programs in the form of excel spreadsheets or PDFs for their followers to download. Most of the programs are claimed to be the way the influencer reached their goals and attained the impressive physique or strength they currently have. There are a lot of excellent programs available, but there are also many subpar programs that aren’t worth your hard-earned cash.

But how can a program be bad? There are a whole range of factors which can affect whether a program is effective or not.

One example would be when a program has been made and/or tested by someone who uses PEDs and isn't educated on how natural lifters should train. These plans are often likely to be ineffective because the substances that this influencer takes make it very easy for them to progress no matter how they train.

This problem is often caused by previously discussed ‘fake natties’, who out of ignorance or lack of knowledge, sell these sorts of programs to their audiences of young, and natural trainees, for monetary gain without knowing the harm they could cause.

Of course, people who take PEDs still work incredibly hard (if not harder) to get where they are, but the limiting factors faced by natural trainees are nonfactors to people using PEDs. Essentially, they could disregard factors such as exercise selection, variation, frequency, intensity, and volume, and still make better gains than a natural trainee. It is worth noting however that professional bodybuilders and experts do take these factors into account to absolutely maximise their training.

The poorly designed programs among these often have so much volume (total number of reps and sets) at such a high intensity, that a natural trainee would not be able to recover and would result in their performance actually regressing instead of progressing.

There are several concrete reasons why a program may not work, however. Dr Mike Israetel; published writer, bodybuilder, and co-founder of the popular Renaissance Periodization YouTube channel; gave his criteria for what makes a perfect program.

“Most folks see the best results between something like ten and twenty working sets [per week] for enhancement of hypertrophy, and then for the enhancement of strength it’s probably more like five to fifteen working sets.”

For frequency, Dr Israetel recommends a range of two to four times per week for most muscle groups, although some can be trained up to six times per week.

“Every session can check the boxes of being hard and challenging but also such that it’s not so hard and challenging that you’re not very recovered by the next session for that muscle to hit it hard again.”

He also spoke on the pitfalls of training to failure too often, and why it’s a waste of time.

“It leads to a very rapid accumulation of fatigue.

“So, the bros on TikTok advocate for failure because they use failure as a psychological proxy for their internal need to push themselves to the limit.”

Israetel expressed his thoughts on subpar online programs, recognising that there are many poor programs out there, but that the consumer is also to blame for not doing their research before “handing out their money”.

“It’s one of those things where, the responsibility I think lies on both sides of the aisle.”

About six months into my time lifting weights, me and a friend completed the same program we bought online together. Over eight weeks, I saw a regression of strength, whilst his skyrocketed. Why is this?

Initially, I put it down to the program itself being poorly constructed. When comparing the program to Dr Mike Israetel’s advice, however, I noticed the only standout negative of the program was that the volume was slightly too high at 23-25 sets per muscle group per week. Regardless of this, why did it negatively affect me, but not my friend?

Mitch is an advanced trainee who has trained with a mixture of bodybuilding and powerlifting style training for now, almost six years. He believes the program worked in his favour but not mine, due to factors that were nothing to do with the creator of the program.

“I’d say I was probably into intermediate level of training.

“I quickly realised… that I needed to be in a slight [calorie] surplus in order to get the most out of it.

“I was eating probably 250 to 300 calories into a surplus.”

As well as making sure he ate enough food, Mitch took other measures to ensure his recovery was on point.

"I was making sure I was mobile enough, getting active recovery on off days."

He also made sure to not make each session too intense.

“I used to go somewhere between two reps or one rep off failure.”

In comparison, at the time I completed the program, I had only been training seriously for roughly six months, meaning I was technically still a beginner. This is one reason why I found it so hard to handle the high volume.

I was also eating in a caloric DEFICIT, another factor that limited my recovery.

This lack of recovery from sessions, in turn, began to increase the intensity. As I got weaker, weights I’d used before started to become harder and harder, meaning to complete the same number of reps, I’d be pushing a lot closer to failure than necessary. This extra fatigue limited my recovery even further.

So overall, yes, the volume of the program may have been slightly high, but in retrospect, the regression in strength I saw from the program was almost entirely down to my own doing. This just goes to show how if a program does not work for you, this does not necessarily make it bad or poorly constructed.

Advice from the experts...

Not all programs are bad. Some are exceptionally good at helping you reach your goals.

- To find a good program, make sure it’s been constructed by someone you trust. This should be an influencer who you can tell has an extensive knowledge of lifting.

- Then look at the program’s reviews. If there isn’t a dedicated reviews section on the page where you purchase the program, it’s likely a red flag. Websites like Reddit can be great for this, as the posts are made by honest and impartial users. Simply search for the program you’re thinking of purchasing followed by ‘Reddit’ to find someone who’s completed it and given their opinion.

- Make sure the program is suited to your goals. Some are more powerlifting based, meaning they aim to help increase your strength as much as possible, and some are more bodybuilding focused, aiming to help you build as much muscle as possible. There are some programs available which incorporate strength and muscle building, known as ‘powerbuilding’.

If you're looking to build size, strength, or both, have a look at Jeff Nippard’s programs. He has an extensive knowledge of programming and tests all of his programs out before selling them at a reasonable price. All of his programs are designed to work depending on your goals and experience level.

If you’re focusing solely on strength, any of Jamal Browner’s 12-week intermediate programs are a good option. Jamal is a world-class powerlifter, who worked closely with StrengthStudioTT to create some very effective programs.