Invisible citizens:

LGBTQ+ Life in Italy

Turin, renowned for its stunning alpine vistas and vibrant ski resorts, is a magnet for winter sports enthusiasts from around the globe.

Each year, the skies over this Italian city are filled with the hum of planes arriving from places like Bristol, creating a scene of joy and anticipation.

Yet, amid this excitement and the charm that draws tourists, Lavinia Calamai’s story reveals a different side of Italy—a darker one.

While many flock to Italy for its allure, numerous Italian LGBTQ+ people, like Lavinia, leave and reluctantly return.

Lavinia is en route to a small, secluded town on the outskirts of Turin, a place she hasn't visited in over a year.

The emotional weight of returning to her hometown is evident. When I asked her why she had left Italy in the first place, her response was: "I left to save my life."

Eight years ago, Lavinia left Italy with little more than hope and determination, seeking refuge in England.

Her departure was not driven by the typical quest for career advancement or adventure, but by a profound necessity.

Lavinia left Italy driven by the feeling that she couldn’t be herself—couldn’t be openly LGBTQ+ in her own country.

"For the Italian state I am a second-class citizen" says Alessandro Diolaiuti.

Unlike Lavinia, Alessandro decided to stay. He says " I prefer to fight from the inside".

However, thoughts of leaving the country have crossed his mind.

“I want to have children, but I know that if I continue living in a country that makes it nearly impossible, I’ll have to leave. That would be a huge failure—just huge.”

He grew up in a small town on the outskirts of Turin, then moved to the city to pursue a degree in Psychology.

He recalls an incident from a few years ago when a protester interrupted a speech by Giorgia Meloni, the Prime Minister of Italy, by holding up an LGBTQ+ banner. In response, Meloni said, "You already have civil unions."

He explains that while this is technically true, it is not because of her support; her party, Brothers of Italy, voted against civil unions in 2016. Furthermore, civil unions are not equal to marriage in terms of rights and legal protections.

“There is no requirement for fidelity,” he explains, “and, most importantly, we do not have the right to adoption or access to medically assisted procreation.”

He concludes, “In 2024, the state still treats me as a second-class citizen in terms of rights but not duties though, I fulfill all my duties and pay taxes like everyone else.”

Growing up, Alessandro says “The word ‘f*ggot’ was often on the lips of my peers.”

“I never brought any boy to Ovada. If I did, it was at times when no one was around. I was afraid of people's reactions.”

He thinks Italy's homophobia stems from legal issues. "It is the fact that we do not have equal legal rights".

ABSENT DATA

Turin was once a beacon of LGBTQ+ rights, but it has now become the city with the most homophobic attacks in Italy.

Over the past year, 23 incidents were reported in Turin alone, far surpassing larger cities like Rome, Milan, and Naples.

The situation is even more alarming when looking at the broader regional picture.

Piedmont, Turin's region, now stands out as the most homophobic in Italy, both in absolute numbers and in proportion to its population.

Piedmont saw a significant surge in violence and harassment against LGBTQ+ people.

But what if I told you none of this data is actually reliable.

This data was collected by an association called ArciGay, which tries to retrieve as much data as possible on LGBTQ+ life in Italy.

The director of the association Flavio Romani describes their search for information as "looking for a needle in a haystack, sifting through news articles, hoping for clarity."

This illustrates the challenge they face: the data is sparse, unreliable, and scattered.

Without any official records or comprehensive reports, organisations like ArciGay are forced to rely on whatever scraps of information they can find in the media, often with little context.

This situation underscores the fundamental issue in Italy: there is no systematic collection of data regarding crimes or discrimination against LGBTQ+ people.

WHY IS THERE NO DATA?

Unlike in the UK, where detailed records can be easily accessed or requested, Italy offers no such transparency.

In Italy the data does not exist.

To understand why, it is important to know a few things.

Firstly homophobic and transphobic attacks are rarely reported in Italy because victims know there is no specific law to protect them.

Italian police and other criminal justice authorities do not record hate crimes specifically motivated by homophobia or transphobia.

Without a law that defines homophobia or transphobia as a crime, there is no official crime category for it.

The data in Italy published by the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) comes from two sources:

- SDI (Sistema di Indagine): A police database that includes crimes with a recognised discriminatory motive, but only those that are covered by existing laws.

- OSCAD (Observatory for Security Against Discriminatory Acts): An Italian observatory that collects reports on discrimination, including homophobia and transphobia, which are not specifically covered by law. However, OSCAD does not gather formal crime reports—it collects informal complaints or reports that victims might submit in addition to or separately from an official police report.

This lack of formal data recording is why homophobic and transphobic hate crimes are often "invisible" in Italy. There is no law requiring them to be tracked, so they are not officially documented.

"MARRIED" BUT NOT MARRIED

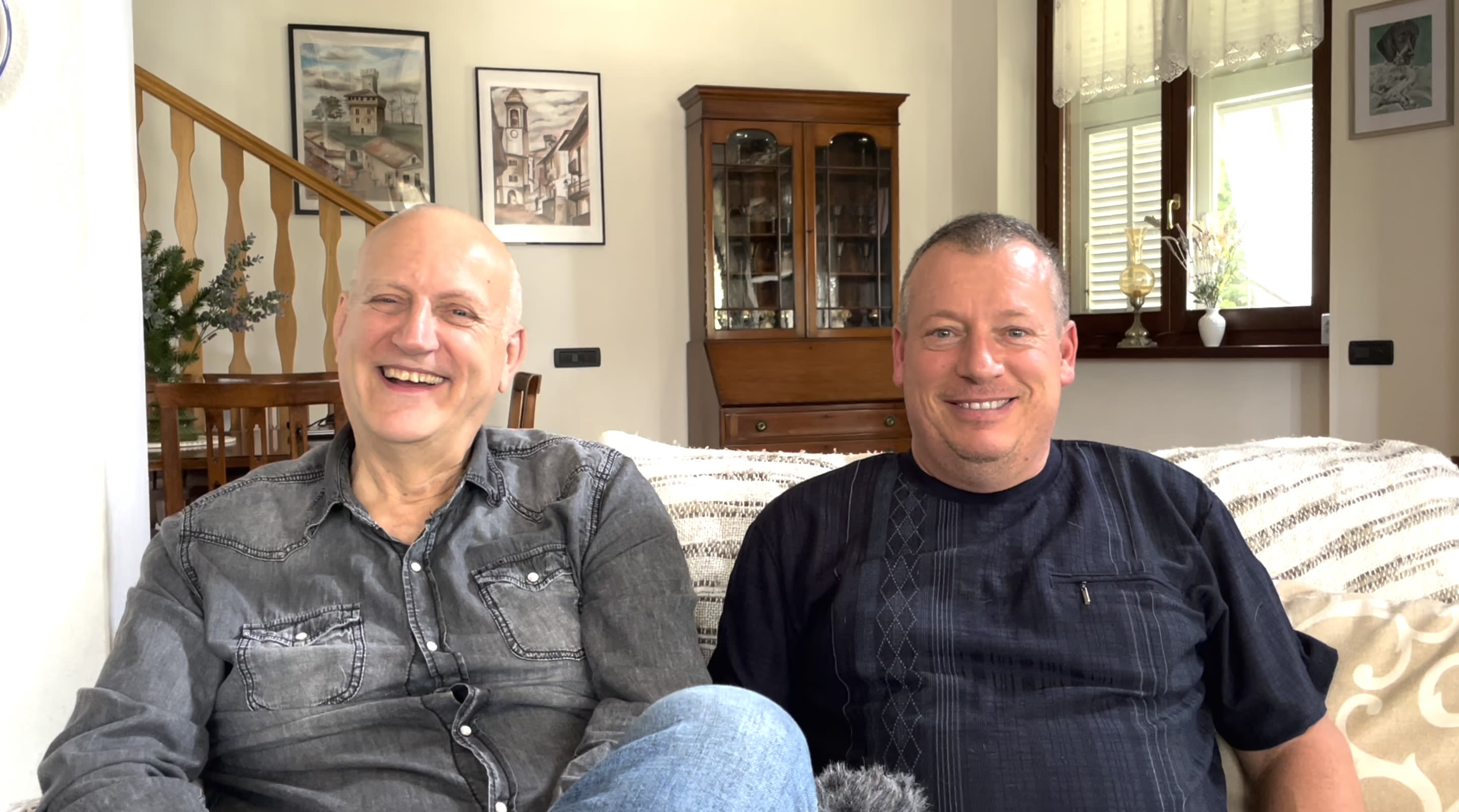

Jeff and Andrea married in a civil union in Italy the year it became legal in 2016, becoming the first gay couple to marry in the Province.

"I would have prefered it to be equivalent to heterosexual relationships, identical, but there are some slight differences" says Jeff.

Jeff and Andrea live in a small village in Piedmont Italy, they have now been running an air B and B there for 20 years.

They moved to Italy after they retired to be close to Andrea's mum.

When they first decided to have a civil union in Italy they faced numerous challenges.

The first challenge unusually was Jeff's paperwork.

Jeff is originally from London in the UK. He says that in the UK "they use the same paperwork as they use for marriages".

However, the Italian authorities wanted them to say civil unions. They didn't because in the UK they are considered equal.

Andrea says "they wouldn't accept the proper word marriage".

Italy is in fact the one of the only countries in Western Europe in which if a person falls in love with someone of their same sex they do have the right to get married.

The next challenges they faced were actually living in the country as a "married" couple.

Jeff says, "You often get raised eyebrows from officials, you can tell they don't like it"

Andrea, who grew up in northern Italy, is even more cautious.

He still finds himself reluctant to reveal to strangers that he has a husband at home. "If you get insulted, there is no law that protects you" he says.

Before moving back to Italy, Andrea admits he had serious reservations about returning to the place where he had faced discrimination as a young gay man.

He had once longed to leave the country to escape the hostile environment he faced for his sexuality.

Now, even with the progress Italy has made, those old fears still linger, and the couple has learned to navigate life in a place where acceptance is still hard-won.

The arduous approval of the law on civil unions, known as the Cirinnà Law, only came in 2016.

After years of heated political debate and opposition from conservative groups and the Catholic Church.

The Cirinnà Law marked a significant step forward for LGBTQ+ rights in Italy, as it allowed same-sex couples to enter into legally recognized civil unions, granting them many of the same rights and protections as heterosexual married couples in areas such as inheritance, pensions, and healthcare.

However, the law still falls short in crucial ways, particularly when it comes to family rights.

The Cirinnà Law does not grant same-sex couples the right to adopt children or access surrogacy, which means they are unable to legally form families through these channels.

Unlike in many other Western European countries, where same-sex couples enjoy full parental rights, Italy remains resistant to recognizing LGBTQ+ family structures.

THE INVISIBLE FAMILIES

Gitana and Benedetta are a same sex family living in Turin.

Because they had their daughter before the general election which saw the party Fratelli d'Italia rise to power, they were able to become an official family.

But under the new administration, new families have no longer been able to register their children.

Gitana says "I want to live in a kind Italy, this country is no longer kind."

Rainbow families in Italy are "invisible by law." Not only does the word "family" not appear in the text of the Cirinnà law, but the lack of legal recognition also makes their statistical detection difficult.

So one knows exactly how many rainbow families live in Italy and data on their lives is sparse.

Gitana and Benedetta say "with this government we have gone backwards and we confess that we are afraid of where our country might go, especially for our family."

Elena Polleti also lives in Turin. She is mother of two and has been married to her partner Silvia for 8 years now.

They had their first child five years ago and had no issue legally registering her. But by the time the second child came, three years later, Italy's political climate had shifted.

Ministers stopped recognising children of same-sex couples.

Elena and her wife had to go through the process of adoption to get their second child's rights.

"Having these rights is important because it means that in emergencies, or if one of the parents dies the child is looked after."

"My wife can't take our child to the doctor's, she wouldn't be recognised as his mum if he had to go to A and E. These things weigh on us".

In Italy there is no national law to protects these families, instead it is up to the different regions to choose their approach.

After the election much more conservative leaders are in power in Italy's regions causing this big shift to families no longer being recognised.

They now have to fight for the recognition of their families in regional courts.

The fight for recognition is a constant source of stress for Elena and her wife. The uncertainty surrounding their legal status as a family has created immense pressure.

"We’re always on edge," Elena explains. "If something happens to me, I want to be sure that my wife can step in without hesitation. But right now, the law doesn’t see it that way."

The lack of national protection means families like theirs are left in a vulnerable position, where the recognition of both parents isn't guaranteed, and they are at the mercy of regional policies that may be biased or discriminatory.

This inconsistency between regions means that while some may be more progressive, others have rolled back the rights and protections that had been previously granted.

With the rise of more conservative leaders across Italy, families like Elena's are finding it harder to gain legal recognition.

What once seemed like small victories in the fight for equality are now being threatened, and the battle is far from over. "We're having to start over in some places" says Elena.

Elena is acutely aware that the fight for equality is a long one, and while they are committed to standing up for their family, it weighs on them heavily.

"We’re not asking for special treatment." she says, "Just the same rights any other family would have. We want to protect our kids, and we shouldn’t have to fight so hard for that."

Despite the obstacles, Elena and her wife continue their legal battle, hoping that one day the law will change at a national level, and their family will be recognized everywhere without question or fear of discrimination.

However, for now Italy's ruling party has maintained a consistent stance on traditional family values and has been criticized for its lack of support for LGBTQ+ rights.

This stance has shaped the political landscape and created a challenging environment for the LGBTQ+ community in Italy.

ITALIAN LAWS AND POLITICS

The ruling party in italy is Fratelli d'Italia (Brother's of Italy) and it is led by Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni.

The party has consistently supported traditional family values and has faced criticism for its lack of support for LGBTQ+ rights.

Leila Talani, an Italian political expert from University College London, explains:

"No one can expect Meloni to be in favour of LGBT rights; she has never been in favour."

Founded in 2012, the Fratelli d'Italia (Brothers of Italy) party promotes conservative values, nationalism, and traditional family structures.

Meloni and Fratelli d'Italia are known for opposing policies that expand LGBTQ+ rights.

Talani says this should be no surprise after all prime Minister Meloni was very clear throughout her campaign about her intentions.

She says Meloni "is doing the policies that she said she would do, so in a way she is very coherent and honest in this."

Policy and Legislative Failures for LGBTQ+ Rights

In 2021, Italy made an attempt to push through legislation aimed at protecting LGBTQ+ individuals from discrimination. The law, known as the DDL Zan bill, sought to criminalize discrimination and violence based on sexual orientation, gender identity, and disability.

However, the bill was fiercely opposed by conservative groups and eventually scrapped after a contentious vote in the Italian Senate. The collapse of the DDL Zan bill was seen by many as a major setback for LGBTQ+ rights in the country.

Fast forward to 2024, and a similar scenario unfolded. Italy, under Meloni’s leadership, refused to sign a European Committee declaration supporting pro-LGBTQ+ policies.

This decision put Italy in alignment with Hungary and Poland, two countries frequently criticized by the European Union for their hardline stance on LGBTQ+ issues.

Diverging Voices Within Fratelli d'Italia

Interestingly, while the national leadership of Fratelli d'Italia remains firm on its conservative stance, some of the local representatives within the party exhibit a more progressive outlook.

Angelo Priolo, alocal candidate of Fratelli d'Italia, offers a different perspective, suggesting that the traditional views on relationships and family are outdated.

Priolo states, "I think these ways of thinking of traditional relationships and families are old ways. I think that with more of the younger generation involved, these ideologies will change also for the party."

However, Priolo also acknowledges the party's reluctance to engage with issues surrounding family and relationships, noting that Fratelli d'Italia "does not involve itself" in such matters.

Gianfranco Baldi in his office

Gianfranco Baldi in his office

Gianfranco Baldi, president of the Alessandria province is another key figure in the Fratelli d'Italia party.

Baldi supports traditional family values but also believes in the importance of personal freedom.

He explains, "While I believe the traditional family model holds its own importance, everyone should be free to make personal choices without facing obstacles or discrimination."

The Challenges Faced by LGBTQ+ Italians

In this challenging political climate, Italy's LGBTQ+ community continues to find ways to navigate around legal and social barriers.

Civil unions have become a legal workaround for same-sex couples wishing to formalize their relationships, but full marriage equality remains elusive.

Many same-sex couples travel abroad to adopt children, only to return to Italy and fight for recognition of their family status in regional courts.

The future of LGBTQ+ rights in Italy remains uncertain. While the ruling government under Meloni shows little sign of shifting its conservative stance, voices like Angelo Priolo’s offer a glimpse of potential change.

As younger generations become more politically active and the discourse around family evolves, there may be room for progress within Fratelli d'Italia and Italian politics more broadly.

However, for now, LGBTQ+ Italians must continue to navigate a legal landscape filled with obstacles, relying on civil unions, regional courts, and activism to assert their rights in a country that has yet to fully embrace them.

The question remains as to whether Italy’s government will eventually follow the path of its European counterparts in granting full equality to its LGBTQ+ citizens, or if it will continue to uphold traditional values at the expense of progress.

For now, the battle for LGBTQ+ rights in Italy is ongoing, with no clear resolution in sight.